Gerrymandering is contended for many reasons. From socio-economic issues, to racial discrimination, gerrymandering has historically shown to be a downwards factor for each. However, in more recent years, political weaponization of redistricting has shown to impact not just a specific group, but every demographic in the United States; today, it has turned into a climate issue.

To understand how it’s so detrimental, we must firm zoom in on the area that’s impacted the most: Ohio. Ohio districts appear in lists of the nations worst examples of gerrymandering, a practice Ohioans tried to control in 2018. But the reforms put in place for the 2021 redistricting process haven’t worked quite as planned. Governor Mike DeWine, a Republican, on November 20 signed off on a new congressional map that shows significant advantage to his party, according to the Princeton Gerrymandering Project, which gave the map a grade of F. Groups like the Women’s voter league of Ohio have claimed that the redistricting commission violated the state Constitution.

Another organization suing the redistricting commission is the Ohio environmental council, a Columbus-based advocacy group. According to staff attorney Chris Tavenor, recent history has shown that the new maps will play a key role in shaping climate action in the state.

“Over the past 10 years we’ve had a supermajority legislature in Ohio pass bill after bill that short-circuits Ohio’s ability to fight climate change,” he said.

Data from the Yale Program on Climate Change Communication show a majority of Ohioans believe climate change is happening and worry about it.

A majority also favor regulating carbon dioxide as a pollutant, imposing strict carbon dioxide limits on coal-fired power plants, and research and tax rebates for renewable energy, according to the Yale data. And 2/3 would also require utilities to produce 20% of their electricity from renewable sources.

Over the last decade, however, Ohio lawmakers have subsidized noncompetitive coal plants and erected additional barriers to siting renewable energy.

The reason why is the same reason lawmakers are elected in the first place. Politcally drawn maps and money. In this case, both are contributing to the RISING emissions in Ohio, despite a need to decrease carbon emissions before the year 2030. In fact, oil and gas companies are lobbying the representatives that twisted the vote.

When Republican state Sen. Michael Rulli took the podium to address his colleagues about a resolution declaring natural gas as “vital” to Ohio’s economy, his rhetoric matched nearly word-for-word what an oil and gas lobbyist sent him privately as a “sample script.”

The oil and gas lobbying disproportionately takes effect through representatives who were said to have “mapped their way to election victory”.

The reason why is simple: when elected officials don’t have to worry about truly winning a reelection campaign, they have less incentive to be responsive to constituents. They also have less incentive to appeal to more demographics, because all they really need to do is appeal to their own party in order to win. This system only perpetuates more polarization in our government. And that only means more focus on party battle, and less focus on the problems that tear apart the citzens that they are supposed to represent.

That lack of true engagement and representation makes people less likely to vote, which further suppresses democracy, Miller said. “Gerrymandering, low voter turnout and high voter frustration all go hand in hand.” Simarly, eradicating one has the power to change the narrative for the others.

“If we’re looking at how to make progress and protect public health and our environment, that shouldn’t be a political issue,” said Miranda Leppla, who heads the environmental law clinic at Case Western Reserve University School of Law.

However, solutions are arising.

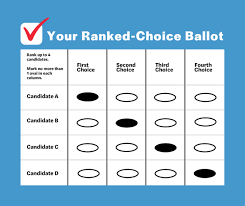

An alternative voting system that could possibly combat the increased polarization is a ranked choice voting system.

Through ranked choice voting, candidates are forced to appeal to a wider variety of people, across all districts. In return, more moderate candidates are incentivized to run for election…and the data shows, they have a better chance of winning too. RCV entails an increase in candidates sending media campaigns to a broader range of people, which forces them to become more moderate since it’s the moderate candidates that have the ability to win

In fact, Bloomington reports that Multi-winner RCV elections allow a larger spectrum of voters to elect their candidates of choice. In multi-winner RCV elections, minority communities and communities with a diversity of backgrounds can elect candidates of choice. This in turn can lead to a more diverse array of candidates. Ranked choice voting opens the election process to new, diverse candidates by eliminating the unrepresentative primary that prematurely narrows the field of candidates before most voters weigh in. Cities that have implemented RCV have seen more women and people of color both run and win.

It also breaks the pattern of gridlock. Since congressional polarization has been on the rise since the 1970s. At the same time, and likely as a consequence of polarization, legislative gridlock has been increasing. Encouraging moderation in elections is key to alleviating this issue.

Furthermore, ranked choice voting provides direct solvency for the climate crisis. Most Americans want more progress on climate action, so anything that makes democracy more representative will likely help expedite policy action on the issue.

That’s because since ranked choice voting better aligns politicians with their constituents (because the victor of a ranked choice voting election has to earn more than 50 percent of the votes), leaders elected under ranked choice voting are much more likely to represent the views of the people in their community than those elected under plurality pick-one voting, who might have very little support (especially if they were elected in a primary).

If elected leaders have better incentives to listen to their constituents’ concerns about climate change, for example, they might be more likely to punish toxic spills, update building codes, and advance clean energy.

Aditionally, ranked choice voting reduces entry barriers for third-party candidates, including those focused on specific issues. A Green Party candidate, for example, can run without fear of taking votes away from a similarly positioned major-party candidate, because voters who choose the Green Party candidate first can have their second choice count if their first choice doesn’t get enough initial votes.

Finally, further research has found that when women are in leadership positions, climate action increases, and that both women and people of color are more likely than other demographics to be concerned about climate change. It follows, then, that ranked choice voting might open the door to more diverse political leaders who will both act on climate change and do so with their communities’ needs in mind.